Lessons on Gender Representation from Pre-school Serial Drama in Ireland

By Izzy Fox, October 30 2024.

Can pre-school animated series teach us anything about gender representation in serial drama made for teenagers? What do creative media professionals working in the animation industry in Ireland think about the challenges and opportunities of achieving on-screen diversity?

A series of twelve interviews were conducted in Ireland, as part of the GEMINI project, with creative media practitioners working in a variety of roles on television drama series, including scriptwriting, directing, producing and show-running. Most of those interviewed wrote for an adult audience, while three interviewees worked primarily on shows created for a younger demographic than GEMINI’s target audience of teenagers, namely, animated series for pre-schoolers. The make-up of our interview cohort reflects both the dearth of serial drama made primarily for the teen market and the concomitant proliferation of children’s TV shows, particularly animation, made in Ireland. However, there are lessons to be learned from the pre-school animation industry in Ireland for those creating and funding drama series for older audiences, including teens, in terms of on-screen gender representation.

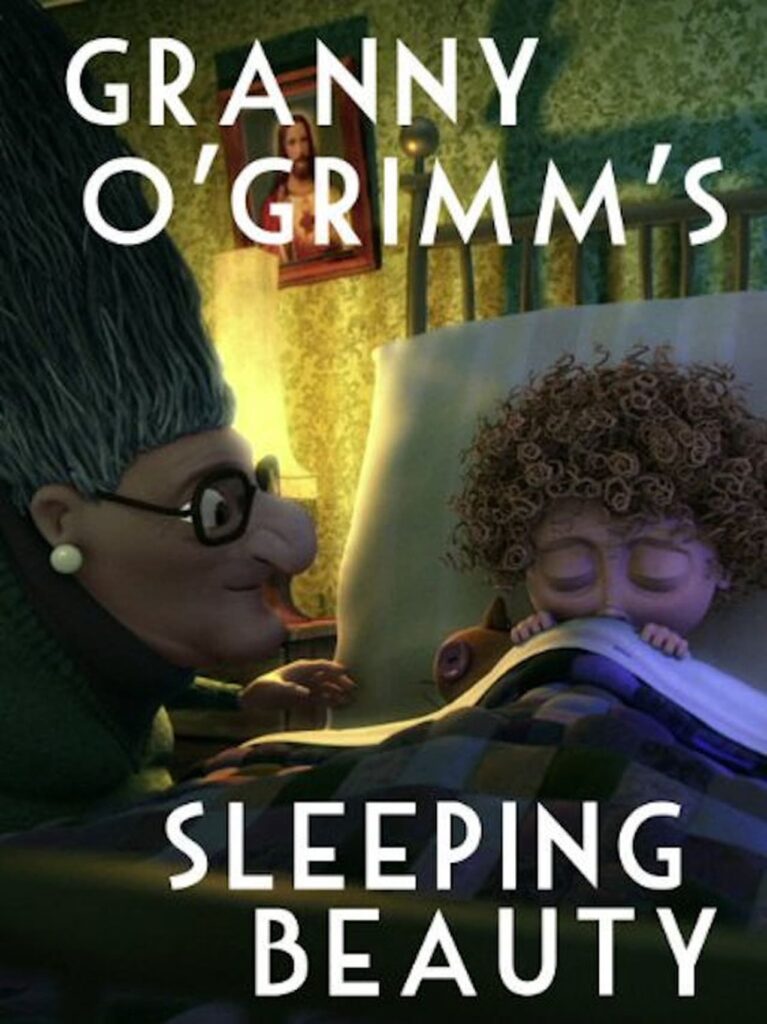

Figure 1: Two of the Oscar nominated films made in Ireland, include the short film Granny O’Grimm’s Sleeping Beauty (2008 Brown Bag Films) and the feature film Song of the Sea (2014 Cartoon Saloon).

Adam Byrne* (showrunner and director) discusses considerations given to gender representation on screen, which relate not just to the numbers of male and female characters in an animated pre-school show but also “the amount of screen time they [get], and what they [are] doing on screen,” as well as what message is being presented through particular representation dynamics (2024). For instance, Byrne highlights the importance of challenging traditional gender roles in serial drama, such as placing male characters in a care-giving role. He also understands that gender is not a binary and that it is equally important to represent trans and non-binary characters on screen, albeit while recognising the challenge of doing this through a medium whereby the characters are often anthropomorphic.

Byrne laments the “ghettoising” of gender that persists in many international pre-school shows, which he observes is “cynically driven” by the market to sell merchandise, even though, there has been a conscious effort in the industry to diversify on-screen representation (2024). However, as Byrne notes, gender roles can be subverted through pre-school series, such as, representing boys with the “same emotional range” as girls (2024). Byrne explains that this has sometimes involved having to flip the gender of certain characters during production in order to achieve this. In addition, important gender issues such as consent and bodily autonomy can also be depicted in shows for such a young audience, through a focus on hugging, for instance.

Decisions on to how to depict such topics in age-appropriate ways, or on which gender a particular character should be, are not exclusively made by the show-runner or other creative professionals working on the show. Instead, it is common, particularly in the animation industry in Ireland, to work in consultation with organisations, such as The Perception Institute, that perform a type of diversity audit on a TV series. While expert groups are consulted, from time-to-time, in the production of TV shows for teens and adults, particularly when a sensitive topic is being presented, it is not a routine practice, with the notable exception of the increased presence of an intimacy coordinator on many film and TV sets.

Furthermore, testing material on audiences while a show is in development is a feature of the production process for many pre-school series. Another interviewee, Beth Coyne*, director and showrunner, referred to the effectiveness of audience testing for a show she had created. This involved showing the pilot of the series to a group of 3-5 year olds with their parents present, assessing the interest level of the children, as well as noting any comments they or their parents made. Coyne claims that the process was particularly effective in seeing at what points in the episode the children’s focus waned or, alternatively, where their interest was piqued (2024). In addition, feedback from parents encouraged Coyne to change the name of one of the main characters, as the original name was a mispronunciation of a common word, which irked them (2024).

From audience testing to consulting experts, there is a lot to be learned from the pre-school animated industry in Ireland for those creating serial drama for teens and adults. Moreover, this point is further supported by feedback from the student focus groups conducted in Ireland, Romania, Italy and Denmark, where most of the teens interviewed recognised the importance of on-screen diversity, while also expressing a desire for a more naturalised representation of gender and sexuality, above a stereotypical one.

Information

* The names of those interviewed have been changed to protect their anonymity