Sex Education and gender-based violence

The nature of a sequence #6

By Maria Elena D’Amelio, 25 June 2024

Sex Education (Netflix 2019-2023) is a coming-of-age comedy drama set in a British high school. It focuses on the sentimental and sexual lives of teenagers. The show centers on a teenager-run sex clinic set up in school by two students, Otis and Maeve. The Italian high school students interviewed for the GEMINI project praised the series for its groundbreaking and inclusive depiction of contemporary teenagers’ sex life and for dealing with socially relevant topics such as consent, body positivity, mental health, queer identities, and feminism.

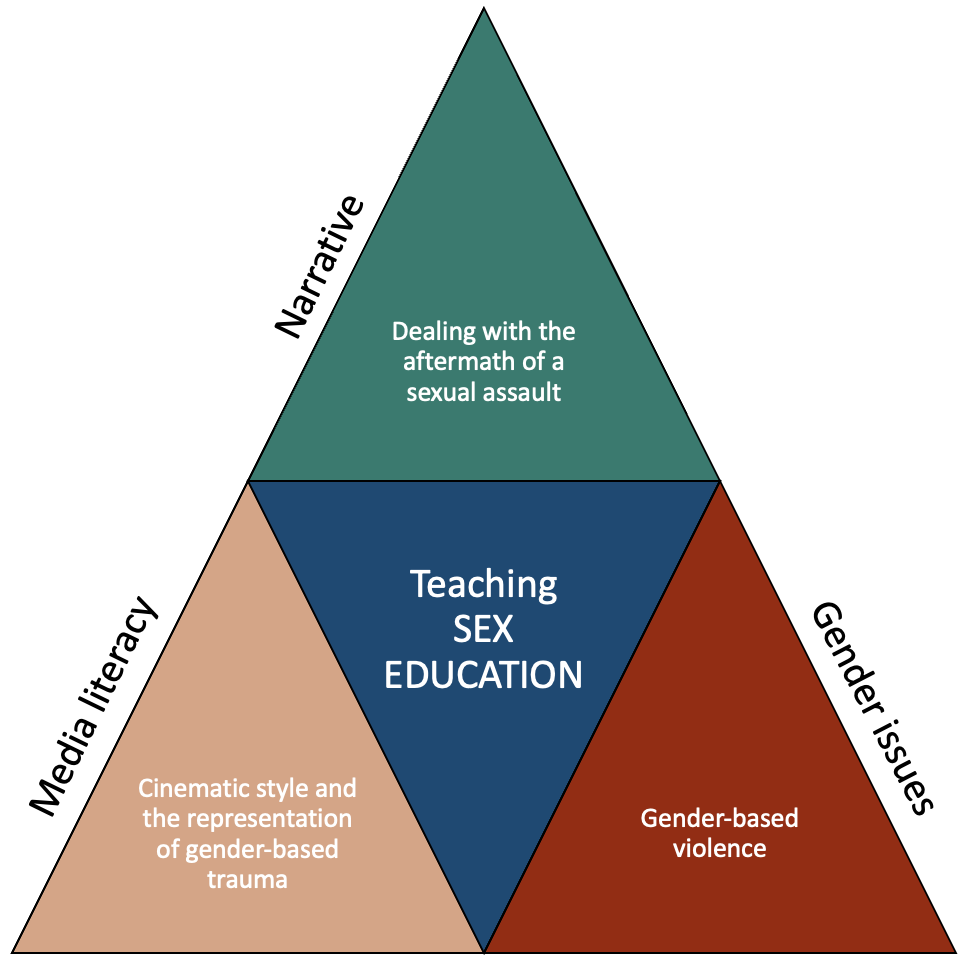

This blog entry applies the “one series, one scene, one issue” approach, which helps facilitate focused discussions on gender issues through a specific scene from a selected series. In this case, it focuses on a particular sequence from the seventh episode in second season, which highlights key themes relevant to the series as a whole, as well as to the GEMINI project itself, such as the representation of gender-based violence.

Background for the sequence

In season 2, Maeve’s best friend Aimee deals with the aftermath of being sexually assaulted on her way to school when a man masturbates on her on a bus. Throughout the season, Aimee downplayed and minimized the attack, despite being traumatized by it and becoming triggered by any physical intimacy. In episode seven, while in detention with five fellow female classmates, Aimee breaks down and admits she can’t get on the bus because of what happened, earning the solidarity of her classmates.

The five girls are in detention because one of them is suspected of having written gender slurs against the English teacher, Miss Sands, who gives them a seemingly impossible task: define what unites them all as women. The girls are all very different in personality, lifestyle, and interests, and do not get along particularly well. At first, it seems they don’t have anything in common until Aimee confesses why she cannot take the bus anymore. At that point, her classmates share their own stories of harassment or assault. After hearing that each of them was subjected to unwanted sexual attention by men at one point in their lives, they realize that what they all have in common is, as one character puts it, “non-consensual penises”.

Pedagogical use of Euphoria in high school teaching

Since GEMINI works towards developing teaching material for European high schools and beyond, this specific sequence from Sex Education can be used as a teaching tool to initiate thematic explorations of sexual violence, trauma and solidarity.

In relation to the narrative structure, the scene deals with the aftermath of a sexual assault and with issues of repressed trauma and PSTD. The sequence demonstrates the importance of a support system that validates your trauma, not only as a requisite to start healing but as a necessary starting point to address gender violence in society. Aimee’s storyline is a realistic depiction of surviving assault, of minimizing and suppressing trauma, withdrawing from physical intimacy, blaming yourself and seeking help to process trauma. It may help students understand and accept their feelings from personal traumatic experiences and assaults, and to understand there are support systems and services.

In terms of media literacy, this specific scene is a suitable example of how complex seriality can provide examples of an effective and respectful cinematic portrayal of gender-violence trauma. The chosen scene indeed handles sensitive topics with care. It doesn’t sensationalize the incident but acknowledges that harassment and assault are an unfortunate reality for many women, focusing on the importance of speaking up and looking for support. For instance, the scene’s cinematic style (close-ups, voice intonation, camera movements) avoids emotionally charged reactions, choosing to emphasize a natural, colloquial tone. Moreover, the shot/reverse shot technique employed in the scene underscores the sympathetic reactions of Aimée’s friends to her story, highlighting the importance of solidarity, validation, and empowerment in the face of trauma.

Finally, in terms of gender issues, the sequence provides an opportunity to foster discussions about gender-based violence and “female understandings of sexual violence” (D’Amelio and Re 2021), questioning and challenging the concept of sexual violence hierarchy and the capacity to recognize that any unwanted and inappropriate sexual approach is considered violence. By sharing their own stories and validating Aimee’s feelings, her friends help her realize that her trauma is real and significant. The sequence highlights the importance of acknowledging and validating one’s own trauma as a crucial step towards healing. It also empowers the viewers, particularly those who may have had similar experiences, by depicting the importance of a supportive and understanding environment.Parts of the above text have also been presented in the GEMINI report “Understanding young adults and gender equality through serial drama” (D3.1). The report will be available through the GEMINI website very soon.

Reference

D’Amelio, Maria Elena and Re, Valentina. “Neither Voiceless Nor Unbelievable: Women Detectives and Rape Culture in Contemporary Italian TV.” MAI 7 (2021).

Watch the full sequence from Sex Educaation through the GEMINI Facebook page.