The Young Offenders and working class masculinity

The nature of a sequence #5

By Izzy Fox, 18 June 2024

“The Young Offenders is about youth and social disadvantage and the persistent tension between the temptation to engage in criminality, get into trouble with peers, and the urge to become morally grounded adults”.

(GEMINI Report, Hansen et al 2024, forthcoming: 26)

The Young Offenders (RTÉ, BBC3 2018 – present) was one of very few Irish serial dramas that also proved to be popular with 15-16 year-old students interviewed as part of the focus groups conducted in post-primary schools in Ireland for the GEMINI research project. The young people referred to the depiction of teenagers in the sitcom and their complicated relationships with their parents as “realistic”. They also liked the two young male protagonists in the show, who one participant described as “[a pair of] messers”. A ‘messer’ is Irish slang for someone who is a bit of a troublemaker but is ultimately harmless and perfectly summarises the antics of teenage best friends, Conor MacSweeney and Jock O’Keefe (played by Alex Murphy and Chris Walley, respectively), who lead the cast.

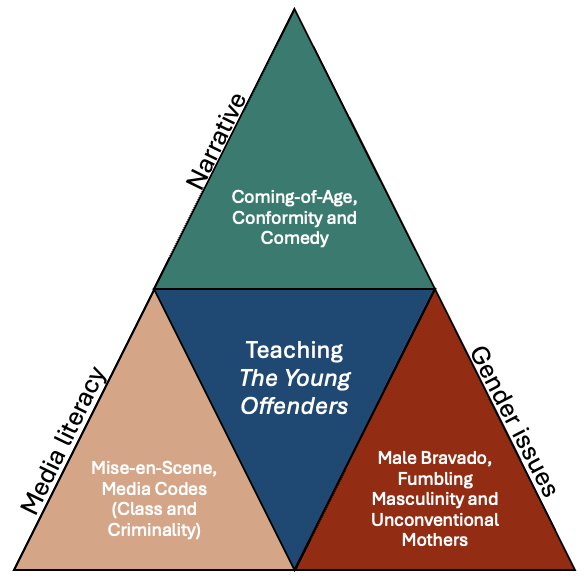

This blog entry focuses on a particular sequence from series 1, episode 4 and highlights key themes relevant to the series as a whole, as well as to the GEMINI project itself, such as the representation of gender stereotypes, heteronormativity, as well as the intersections of class and masculinity. In addition, as a coming-of-age narrative, with features of the “bromance” (a portmanteau of ‘brother’ and ‘romance’) genre, The Young Offenders is particularly suited to our target audience of teenagers and the sequence chosen provides a useful pedagogical exemplar for teaching gender issues through serial drama to high school students.

Background to the series

Conor and Jock live in a disadvantaged area of Cork City in the south-west of Ireland and have a dislike for authority, which manifests in anti-social behaviour at times but, as the ‘messer’ epithet implies, there is usually no malicious intent behind their actions. Conor’s mother, Mairéad, is a young widow and the only stable parent figure in the lives of both boys, as Conor’s father died in a workplace accident, while Jock’s mother is dead and his father is an abusive alcoholic. Even though Jock’s precarious home life leads to him eventually being fostered by Conor’s mother, Conor consistently follows Jock’s lead, wanting to impress his more confident best friend. The description of the sequence that follows highlights the power and gender dynamics at play between Mairéad, Conor and Jock.

The sequence (S1:E4) focuses on the trio as they take a road trip to the west Cork village of Skibbereen to buy a new (or rather “an old bargain”) fridge. The scene in question sees Mairéad driving the car, with Conor in the front passenger seat and Jock positioned between the two, looking grumpy as he is relegated to the back seat, having been blamed for causing the puncture they managed to repair in the scene before; a scene loaded with slapstick humour and witty dialogue. This particular sequence begins with the three characters driving in silence, with the only sounds being that of the car engine and instrumental music playing softly in the background. The relative silence is interrupted by a message notification on Conor’s phone.

The text message is from Linda, a girl from his school, and includes a photo of her in a facemask with her tongue sticking out, asking: “Like my new look?”. Mairéad wonders if Linda is Conor’s “girlfriend”, to which Jock pipes up, “never going to happen,” and accuses Conor of being “frigid”, as he won’t pursue Linda, even though she likes him. This upsets Conor and he defends himself, claiming he is just “shy”. Jock mocks him further by asking, “what’s the fuckin’ difference?” Conor is clearly frustrated at his inability to defend himself against Jock’s insults, as evidenced by his facial expressions.

Jock continues to mock Conor by stating that “girls don’t like frigid guys”, which prompts Mairéad’s stinging retort and attempt to put Jock in his place, a feat which consistently eludes Conor, as she snaps: “they don’t like randy little pricks like you, either”. However, Jock takes the moniker “randy” as a badge of honour and smiles, while awarding himself a 9/10 on the “randy scale”. Jock then turns his attention to Mairéad, asking her “how randy are you?”, and wonders if she is “frigid” too like her son or “randy” like him, which embarrasses Conor further. Conor is very honest about his strong feelings for Linda, when his mother asks him if he likes her. The sequence ends with Mairéad encouraging Conor to pursue Linda, by advising him to use the condom that he has been carrying around with him when he needs it, rather than handing it to her to be confiscated.

Pedagogical use of The Young Offenders in high school teaching

The Young Offenders is a coming-of-age narrative which makes it particularly suitable as a teaching aid for use with high school students, as it contains many themes relevant to this age group, including the rites of passage associated with entering adulthood, such as overcoming adversity, leaving home, resistance to authority, falling in and out of love, as well as crises of identity. The sequence in question is an effective exemplar of some of these features, particularly the latter two.

The uncertainty and desire to fit in amongst one’s peers is commonly associated with teenagers’ coming-of-age, exemplified by sartorial choices, haircuts, lingo and behaviour. This conformity to a norm, albeit one that is associated with an underclass, can be seen in the presentation, demeanour and dialogue of Conor and Jock, as they embody an exaggerated stereotype of a working class teenage boy. For instance, Conor attempts to compensate for his self-confessed shyness by emulating his more confident, sexually experienced and performatively masculine best friend, with comedic effect, as evidenced by their near-identical appearance (Figure 1).

The dialogue between the three in the road trip sequence highlights the informal and candid relationship that the boys have with Mairéad, as they talk about sex and relationships with her, without fear of reprimand. She also speaks in their vernacular, uses expletives, and engages in witty banter with them. This underscores their unconventional relationship with Mairéad, which at times is more like a friendship than one of a parent/adult-child, which flattens out the generational divide between the three characters.

The mise-en-scene of this sequence symbolises the complex yet close dynamic of the trio, as they are packed into a tiny car, a setting which heightens the humour and tension between them. The size, condition and age of the car is as much a symbol of the social disadvantage of its passengers, as their physical appearance and dialogue. In addition, the boys’ attire of tracksuits and hoodies, which is coded as criminal when worn by working class boys, represents a useful entry point for teaching students about the intersectional impact on this demographic when such classed and gendered stereotypes are applied.

Furthermore, while Jock’s bravado usually intimidates Conor, the moment he describes Linda, saying “she’s not like most girls” and that “there’s no bullshit with her”, represents a rare occasion when Conor stands up to his friend. Conor’s sensitivity and resistance to Jock’s authority over him in this instance assures Mairéad and the audience that his feelings toward Linda are more healthy and mature than Jock seems capable of possessing.

While The Young Offenders certainly contains features characteristic of the “bromance” narrative, including “assumed heteronormativity and normative family structures” (Hansen et al, 2024), it resists repeating overtly homophobic tropes often present in that genre (McIntyre 2022). Moreover, Clark’s analysis of the representation of masculinity in the British coming-of-age sitcom The Inbetweeners, is equally relevant to The Young Offenders, as the author states: “[the young male protagonists] do not embody the successful masculine subject, rather they exhibit a kind of heterosexual fumbling” (Clark 3 2018). This representation of masculinity as fumbling, foolish and funny offers interesting ground for the use of this series as a pedagogical tool for teaching gender issues, particularly as it contrasts to representations of absent or abusive fathers, which also feature in this series.

The humour, irreverence and warmth of the dialogue, scenarios and characters in the series, together with the depiction of working class teenage boys in this coming-of-age comedy-drama ensures that The Young Offenders is an important media text to use as a tool to teach gender issues to high school students.

The choice of this sequence was inspired by the as yet unpublished doctoral thesis of Sarah Larkin, Media Studies, Maynooth University.

Parts of the above text has also been presented in the GEMINI report “Understanding young adults and gender equality through serial drama” (D3.1). The report will be available through the GEMINI website very soon.

References

Clark, J. (2018). “There’s Plenty More Clunge in the Sea”: Boyhood Masculinities and Sexual Talk. Sage open, 8(2), 2158244018769756.

Guerin, Harry. “Behind the Scenes with The Young Offenders.” RTÉ Entertainment, February 12, 2018. Accessed on: https://www.rte.ie/entertainment/television/2018/0210/939519-behind-the-scenes-with-the-young-offenders/

Hansen, Kim Toft et al. “Understanding young adults and gender equality through serial drama”. Report. Forthcoming 2024. Available at: https://gemini.unilink.it/delivables/

McIntyre, A.P. (2022). Derry Girls and Cork Boys: Second Cities, Regional Identities and (Trans)National Tensions in the Contemporary Irish Sitcom. In: Contemporary Irish Popular Culture. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94255-7_3

Watch the full sequence from The Young Offenders through the GEMINI Facebook page.