Netflix’s Adolescence

Gender topics and gendered representation

By Sarah Arnold and Silvia Fanti, April 8 2025

Adolescence (Netflix 2025), the four part limited show created by Jack Thorne and Stephen Graham, follows the aftermath of a murder of a young girl Katie committed by Jamie, a thirteen year old boy, both of whom attended the same school. Each episode takes the perspective of those who come to be involved in the arrest and later detention of Jamie including: police detectives Luke and Misha and Jamies’ father Eddie in episode one; the same detectives visiting a school to investigate the murder and question students in episode two; a psychologist, Briony, tasked with meeting Jamie to ascertain his understanding and awareness of his actions in episode three; and Jamie’s parents, Eddie and Manda, and sister, Lisa, who attempt to normalise their lives while Jamie awaits trial in episode four.

As each episode develops, possible clues as to why Jamie murdered Katie are revealed although never overtly identified as clear contributors including: parental distraction and lack of awareness about their children’s activities and behaviours, paternal aggression and violence, bullying, social media usage amongst young people, and especially incel culture that manifests and circulates on social media eventually transforming into ‘real life’ actions.

Making sense of murder

Importantly, and what has generated some debate, the show largely takes the perspective of adults who try to make sense of the shocking murder that seems initially to happen out of nowhere. Adults become the investigators of both Jamie and young people more generally, learning about, for example, what adolescents are really watching while on their computers in their bedrooms, what are the meanings attributed to emojis among young people, and what form and shape bullying takes in modern society.

Young people themselves are not the narrative agents in this show. They are the objects of study for a fairly clueless world of adults. Murderer Jamie features little by the end of the show. The young female murder victim, as usual in crime drama, is spoken of but never present. Only glimpses of other young people are offered, where they either mislead or enlighten adults about the circumstances around the murder as well as how young people interact and engage with each other.

Necessary conversation or perspectives of men

Press and scholarly attention to the show has been somewhat divided. The press has mostly described the show as promoting necessary conversations about the impact of the manosphere and its association with misogyny among young men, perpetuated and facilitated by social media platforms. Others, particularly academics, accuse the show of perpetuating the very invisibilising and silence of women by men that the show also claims to be concerned about.

Although many claim that the very point is to centre the male perspective and examine male violence, as Sophie Wilkinson writes, “what’s the point in caring about the consequences of [male] anger – the dead girl at the centre of the story, the women existing in misogynist spaces – when so many of the crucial female characters are just not worth caring about?”

It is possible to analyse Adolescence, therefore, for what it foregrounds and prioritises through its visual and narrative storytelling as well as for what it negates and underrepresents. This is a show that speaks about men, largely through the perspective of men, with little to say or attend to in terms of those women subject to male aggression and domination. For example, although Jamie is revealed to have been bullied by Katie, there’s much less focus on how Katie was impacted by the circulation of sexual images on social media by her male peers.

Psychology of the manosphere

Likewise, psychologist Briony is clearly frightened and disturbed by Jamie’s behaviour, but there is no insight into how repeated exposure to male aggression can impact women in the long term. Finally, the closest actual representation of women’s experience of male aggression is Manda’s subjection to Eddie’s emotional outbursts and controlling behaviour, which she has to de-escalate.

Despite these criticisms – indeed, perhaps because of them – the show is an interesting and valuable object of study regarding media, gender and violence. One can, of course, be inspired to discuss the topics that the show represents – the manosphere, bullying, social media, etc. – but also subject the show itself to debate and analysis. This approach to Adolescence does require something forethought.

Joanne Orlando of Western Sydney University, for example, writes in The Conversation that we should be cautious about how to leverage the show as a pedagogical tool for young people. She suggests that if parents are going to watch it with their children as a way of facilitating conversation about ‘gender, identity and online influences’, that this could be framed around discussion about what and why certain ideas about gender appeal to them and their peers, and what kinds of voices and perspectives are underrepresented in the show.

Pedagogical utilisation of Adolescence

Similarly, we in the GEMINI project urge a critical approach to using serial drama as a pedagogical tool. While the show has, indeed, provoked valuable and urgent questions about male violence, teen culture and social media, it is nonetheless a constructed piece of media that must be subject to analysis and critique.

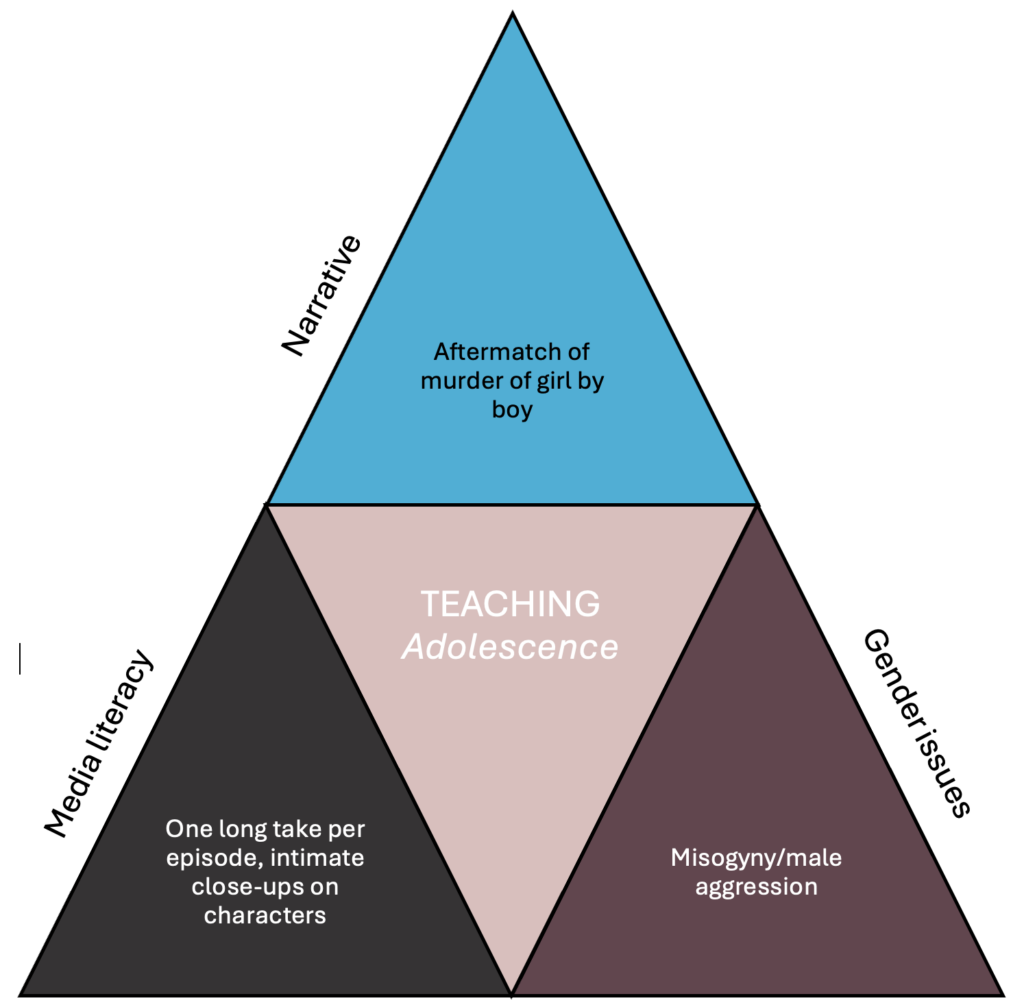

One of the tools using in the GEMINI project is the GMN Triangle, which is a tool that uses a chosen sequence of a show to investigate the ‘media literacy’ the ‘narrative’ techniques adopted within the sequence and the ‘gender’ perspective taken in the sequence. This facilitates discussion among students and teachers about the gender issues themselves and their mediatization. The show Adolescence provides many such sequences that could be adopted for use using the GMN Triangle, and below we showcase how this can be used by teachers.

Adolescence is not just a miniseries loosely based on real-life news events but a deep investigation into the social dynamics that make such events possible. The starting point is the murder of a girl by a classmate, but the real focus of the narrative is the context that led to this tragedy: bullying, cyberbullying, and the influence of the incel subculture on younger generations.

One-shot claustrophobia

The story unfolds over four episodes, filmed entirely in a single continuous shot. This technical choice is not merely a directorial virtuosity but a narrative device that immerses the viewer in the claustrophobia of a nightmare that concerns us all. Because living is hard. Relating to others is even harder. Communicating, understanding, growing up—everything is complex. Being a family, a community, decent people, or even just innocent, is a daily struggle.

Adolescence pins us down in the struggle to exist in the world, regardless of age, role, or social position: teacher or student, police officer or criminal, father, son, sister, victim, or perpetrator. The camera never pulls away, forcing us to watch, to be present, to feel part of the scene. Then, Adolescence delivers a chilling truth, undeniable in its simplicity. It does so through Jamie, the thirteen-year-old protagonist (but not the only protagonist, because we all are, including us viewers).

Distress of a generation

At the end of a gruelling session with the psychologist, Jamie asks: “Do you like me?” “You’ll come back to see me?” Because being seen and, perhaps, appreciated is the only thing that truly matters. At 13, but also at 20, 30, or 80. Adolescence—or rather, adolescences, all of them—is a transitional age, an extreme and cryptic territory filled with violence and fragility, tenderness and contradictions. And it serves as a pretext to remind us how powerless and inadequate we are, even when we believe ourselves to be whole.

Adolescence perfectly represents the distress of a generation locked in their own room, where parents delude themselves into thinking their children are safe, while in reality, their children are in the most vulnerable place possible—with a computer screen projecting them into the world, but at an immature age, unable to judge events that sometimes overwhelm them. Given stark world of adolescence that this series represents, it is no surprise that the series has been the subject of much public attention and debate.

The ’what’ and the ‘how’ of Adolescence

Following on from the above discussion of the debates about the didactic potential of the series, it’s possible to analyse and critique what the show represents – the aftermath of a murder and the attempts by the community to understand it – as well as how it represents it – the narrativisation and mediation of this story.

Here we can use a key pedagogical tool that has been adopted by the GEMINI project – the GMN Triangle, which focuses on narrative, media literacy and gender in a scene or sequence. Gender is overtly represented in the representation of young male violence. This is mediated through close-ups and a roving camera that emphasises this anger, and the narrative that captures the gulf between men and women, as well as adults and youths.

Fractures between people and institutions

In one of the most emblematic scenes of the series, Briony Ariston, the school psychologist, informs Jamie that she can no longer continue their sessions. It is a moment of great psychological intensity: Jamie’s fragility erupts into frustration and anger, revealing a deeply rooted sense of inferiority and a desperate search for validation. The central theme is not just the obsession with physical appearance and self-perception but the difficulty of coping with rejection and loss of control.

Narrative, media and gender issues

A focus on the narrative reveals that the relationship that Jamie perceived to exist between him and Briony is non-existent. This proves, to him, his unworthiness, destroys his trust and confirms what he had thought all along – that he is not interesting and attractive enough to women. The tension between adult and child and female and male erupts here, with Briony withdrawing from Jamie and Jamie enacting his rage.

A focus on the formal techniques – the media literacy perspective – reveals both the power dynamics at play and the intimacy and vulnerability of the characters. Briony is out of frame when she delivers the news he finds so troubling. Jamies reaction are captured first, in panic and confusion. When she is eventually in shot, she ‘talks down’ to him, her facial expression suggesting indifference we know is not accurate – she is in fact terrified by him, but cannot reveal this. He looks up at her imploring and begging her to provide validation that their relationship has been real, that she likes him.

As his desperation and anger build, the camera moves in closely, both it and Jamie shaking erratically, emphasising how unstable he is. And of course, the gender issues are overt and resemble the saying “men are afraid that women will laugh at them, women are afraid that men will kill them.” Briony, once her professional duties are complete, withdraws her attention to and engagement with Jamie. Once Jamie is dragged out of the meeting room shouting, Briony gasps in fear and has to take a break, clearly overwhelmed by Jamie. Her well-founded fear is that Jamie will attack her. Jamie’s fear is that she does not truly like him.

Further avenues of exploration

This scene also provides other useful avenues of exploration. It marks a fracture between institutions and young people. Briony faces an ethical dilemma: her decision to end Jamie’s therapy is professionally necessary but leaves him with a profound sense of abandonment. She is not just a character but the symbol of the collective failure of a society unable to provide adequate support for adolescent distress. This scene, therefore, provides many learning opportunities and opens up room for debate and discussion about where power resides (wo/men, institutions, adults/children).

It is a useful pedagogical tool for adults and young people to understand the message of the series, but also its means of conveying this message through is representations.